-

Syndiquez-vous

-

Articles

Articles

-

Blogs

Blogs

-

Forums

Forums

-

votre référence :

[1996g] (with Danièle Leborgne) " Social and Ecological Impact of Globalization ", Colloque Globalization : What It is and its Implications, São Paulo, 23-24 Mai. To be published in A. Zini & J. Sachs, M.I.T. Press.

Deutsch : Das Argument, Décembre 1996.

Français : in Heurley J. (ed) Les chemins du développement régional, L’Harmattan (à paraître).

Español : in Benko et al. (eds) Economia, Politica y Espaço, Buenos Aires, à paraître.

by Alain Lipietz , Danièle Leborgne | 23 May 1996

Social and Ecological Impact of Globalization

ARTICLE LANGUAGE AND TRANSLATIONS :

Language for this article: English

-

Deutsch

:

[1996g-al] Das Argument, Décembre 1996.

En français " Social and Ecological Impact of Globalization ", Colloque Globalization : What It is and its Implications, São Paulo, 23-24 Mai. A paraître :

Coll. A. Zini & J. Sachs, M.I.T. Press.

Coll. En français : in Heurley J. (ed) Les chemins du développement régional, L’Harmattan (à paraître).

Coll. En espagnol : in Benko et al. (eds) Economia, Politica y Espaço, Buenos Aires à paraître.

|

[1996g] (with Danièle Leborgne) " Social and Ecological Impact of Globalization ", Colloque Globalization : What It is and its Implications, São Paulo, 23-24 Mai. To be published in A. Zini & J. Sachs, M.I.T. Press.

Deutsch : Das Argument, Décembre 1996. Français : in Heurley J. (ed) Les chemins du développement régional, L’Harmattan (à paraître). Español : in Benko et al. (eds) Economia, Politica y Espaço, Buenos Aires à paraître. |

Since the crisis of the Seventies, the developed countries have looked at various ways to construct an alternative. Some have preferred "flexibility", others "mobilization of human resources". Newly industrialised countries have increased their competitiveness and have differentiated themselves according to the same trends. Thus globalization did not lead to an homogenization of national trajectories.

In the first section we look at the different ways the developed countries have attempted to escape from the crisis. In section 2 we dedicate to the case of Newly Industrializing Countries. Section 3 presents the new economic hierarchy. Section 4 evaluates the social consequences of this process, and section 5 the result of it regarding attitudes towards global ecological crises.

I - THE CENTRAL CRISIS OF FORDISM AND THE WAYS OUT OF IT

Throughout the post World War II period, capitalism in the "North West" of the world (OECD) was experiencing its Golden Age. The development model of the Golden Age (which is here called "Fordism") has been in a state of crisis during the 1970s and 1980s, but no one thinks of it as being "the final crisis of capitalism". On the contrary many reforms have been proposed for capitalism, and at the end of the 1980s these reforms seem to have come together to give more or less promising results.

1°) The rise and fall of the Golden Age [1]

First a brief reminder of what Fordism is. As with any model of economic development it can be analysed on three levels.

× As the general principle for the organization of labour (or "industrial paradigm"), Fordism is Taylorism plus mechanisation. Taylorism implies a strict separation between on the one hand the conception of the production process, which is the task of the Organization and Methods Office, and on the other hand the execution on the shopfloor, of standardized and formerly defined tasks.

× In so far as it is a macroeconomic structure (or regime of accumulation), Fordism implied that the productivity gains resulting from these organizational principles were matched by on the one hand a growth of investment financed out of profits and on the other hand a growth in the purchasing power of workers wages.

× In so far as it is a system of rules of the game (or as a mode of regulation), Fordism implied long term contractual wage relations, with strict limits on redundancies, and a programming of the growth of wages indexed on prices and the general growth of productivity. What is more, a vast socialisation of incomes through the Welfare State assured a guaranteed income for wage earners.

The success of the Golden Age model was thus wage-led in the internal market of each advanced capitalist country. There were only limited external constraints because of the limited importance of the growth of international trade relative to the growth of the internal markets, and because of the hegemony of the United States.

Nevertheless, at the end of the 1960s, the stability of the Golden Age growth path was beginning to be questioned. The first and the most obvious reason appeared on the "demand side". There was little competitive difference left between the United States, Europe and Japan. The search for economies of scale resulted in an internationalisation of production and of markets : hence the famous globalization. The regulation of the growth of the internal markets through the wage policy was compromised by the need to balance external trade.

In fact the growth of real wages slowed down spectatularly in the seventies, more and more firms moved their plants to non-unionised zones, or subcontracted in third world countries : once again boostering globalization. But the basic structures of the existing mode of regulation were maintained in the advanced capitalist countries.

However, at the end of the 1970s, there was a change in the state of mind of the international elites of the capitalist world. The management of the crisis by demand side policies had certainly avoided a depression. But a major limitation appeared, the fall in profitability. This was due to a number of "supply side" reasons: the slow down in productivity growth, the growth in the total price of labour (including the indirect wages of the Welfare State), growth in the capital/output ratio and growth in the relative price of raw materials. In these conditions the Keynesian recipes, such as the growth in real wages (however limited it might have been) and lax monetary policy, could only lead to inflation and the erosion of the value of monetary reserves, in particular the international money - the dollar (LIPIETZ [1985]). Hence the turn to "supply side policies", that is to say towards "labour relations", a sphere which has certain aspects in common with the industrial paradigm and the mode of regulation.

Even within the theoretical framework used here, the supply side problems encountered by Fordism can be interpreted in two different ways. In the first, following the tradition going back to Kalecki, the growth in the relative price of labour and raw materials is considered to be the result of the long boom of the Golden Age. The profit squeeze was the result of the proceeding expansion and of full employment. Furthermore, the Welfare State had spectactularly reduced the cost of job loss (BOWLES [1985]), which could also explain the slowdown in the growth of productivity.

At the end of the 1970s, the profit squeeze analysis had become the official explanation. Profits were too low because workers (and raw materials exporters) were too powerful. This in turn was because the rules of the game were too "rigid". In other words, the "rigid" social compromises were to be repudiated.

This policy of "liberal flexibility" was carried out by the British and then the US governments, and was finally followed by most of the OECD countries including the French Socialist/Communist government in the eighties. The renunciation of the social compromise was carried out to different extents and conducted on different fronts - from the rules concerning wage increases (inflation plus productivity) to the extent and depth of social provision, from the liberalisation of redundancy proceedures to the proliferation of precarious employment. This process was carried in an authoritarian manner (governments and management grasped the opportunities provided by the defeats of the trade unions and the political successes of conservative parties) or as a result of negotiations between capital and labour in a context of a rising cost of job loss (for the workers).

After a first period of recession at the beginning of the 1980s, the was a recovery starting in 1983. However this upturn was largely the result of a return to Keynesian budgetary policies (LIPIETZ [1987, 1992]) and it is difficult to affirm that it was solely the result of the liberal policies of flexibility. Moreover the experience of the 1980s did not favour the most serious attempts at flexibility - the United States, United Kingdom and France. On the contrary these countries have experienced both deindustrialization and a worsening of the balance of trade in manufactured goods. At the end of the 1980s, the winners in the competitive struggle (Japan, West Germany, the European Free Trade Agreement) appeared to be characterised by other solutions to the supply crisis.

Returning to "the supply side" explanation of the crisis of Fordism, an alternative to the "full employment profit squeeze" theory explanation insists on a reduction in the efficiency of Taylorist principles. Full employment can explain the fall in the rate of profit at the end of the 1960s, but not the continuation of this tendency, with a growing capital coefficient, in the following years. More importantly, the elimination of all involvement of shopfloor workers in the tuning of the production process now seems to be of limited value. It is a good method for ensuring that management has control over the intensity of labour. But greater "responsible autonomy" of shopfloor workers can lead to a superior organizational principle, especially when it is a case of setting in motion new technologies, or "just-in-time" management of production flows, which requires the involvement of the intelligence of shopfloor workers and their willing cooperation with management and engineers [2]. This was precisely the alternative way chosen by numerous large companies in Japan, Germany and Scandinavia. There, pressure from the unions and organizational traditions led to the choice of the solution by negociated involvement to the crisis of Fordism.

At the end of the 1980s the superiority of this choice is being more and more recognised, not only among this second group of countries, but also in books on management and in the press. Certainly, the international competitive success of this second group has played an important role in this evolution of ideas, but the difficulties encountered in the setting up of the new technologies in the context of liberal flexibility have also encourage a change in management style. However it seems possible that liberal flexibility and negociated involvement are policies that could be combined à la carte. This idea is the basis of a conception of "post Fordism" as "flexible specialisation", as found in PIORE & SABEL [1984]. The mutual coherence of these ideas will now be looked at.

2°) After Fordism, What? [3]

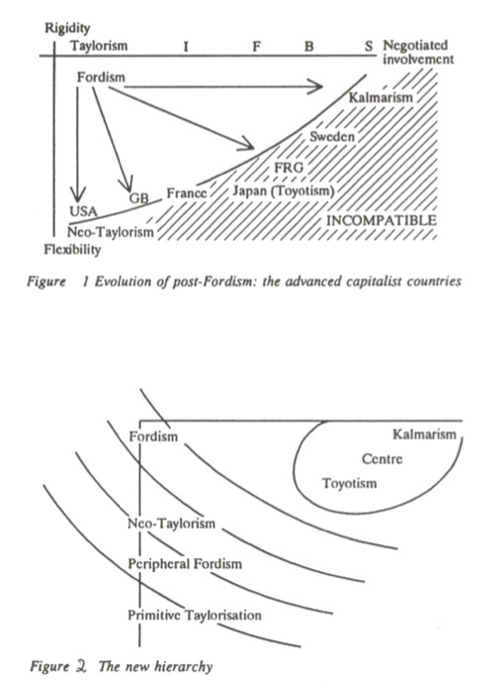

In fact the two doctrines for getting out of the supply crisis can be considered as two escape routes related to the two characteristics of Fordist labour relations. On the one hand the rigidity of the wage contract, on the other Taylorism as a form of direct management control over the activity of workers (see figure 1).

The first doctrine proposes an evolution from "rigidity" towards "flexibility" in the employment contract, and the second an evolution from "direct control" towards "responsible autonomy". Using a different vocabulary (Doringer & Piore [1971]), the first axis refers to the "external labour market", to the link between the firms and the labour looking for work and wages. The second axis refers to the "internal market", to the form of organization of cooperation/hierarchy within firms. On the first "external" axis both rigidity and flexibility have many dimensions, as has already been remarked. The rules of the game may include the rules about the way direct wages are formed, the rules on hiring and firing, the rules on the allocation of the indirect wage - the external market is a more or less organised one. The axis is thus a synthetic axis. Moreover, the rules can be established at various levels - the individual, the firm, the sector, or society as a whole.

On the second "internal" axis, there are also many dimensions: "involvement" may signify qualification, cooperation between workers, participation in the definition and monitoring of tasks etc. Here again it is a case of a synthetic axis. But this time, for reasons which will become apparent, it is necessary to take into account the level of the negotiation about the involvement of the workers.

. The involvement can be negotiated individually and satisfied by, for example, bonuses or promotion systems. This option is limited though by the collective nature of the involvement required in most of the processes of cooperative production. This remains compatible with a flexible work contract.

. The involvement can be negociated firm by firm, between management and unions (F in figure 1). Here the firm and its labour force share the rewards of specific skills accumulated over the course of a collective learning process. This implies an external rigidity of the wage contract, that is limits on the right to fire workers already in the firm, but this compromise clearly does not include workers outside the firm.

× The involvement can be negotiated at the industry level (B in figure 1), this limits the risk to firms of competition through "social dumping", and encourages them to set up communal institutions for training etc. As a consequence the external labour market is likely to be more organised, and in general more rigid and with a greater socialisation of labour income.

× The involvement can be negotiated at the level of society as a whole (S in figure 1), with the unions and the employers organizations negociating the social orientation and the sharing of production at the regional or national [4] level, it being understood that the unions will ensure that "their people" will do their best on the shopfloor or in the office. Here the external labour market is likely to be at least as well organised as in the more corporatist or social-democratic forms of Fordism.

On the other hand, the collective involvement of workers can only occur if firms and the workforce share common aims, in a context of external flexibility at whatever level (individual firms, industry or territory). Thus the limit of the consistency between flexibility and involvement appears as a curve joining the two axes. Outside the curve is an excluded triangular region of inconsistency, where flexibility and negotiated collective involvement are supposed to coexist [5]. The two axes themselves constitute the privileged lines of evolution, that is to say two real paradigms :

× External flexibility associated with direct hierarchical control. This leads to some kind of Taylorist form of organization of the labour process, without the social counterparts of Golden Age Fordism. We call this paradigm "neo-taylorism".

× External rigidity of the work contract associated with the negociated involvement of the producers. We call this paradigm "Kalmarist", in honour of the first car factory (Volvo) reorganised following these principles in a social-democratic country - Sweden.

The recent experience of the OECD countries can be analysed as follows. They-appear to lie on a curve, with the USA and Great Britain prefering flexibility and ignoring involvement, some countries such as France introducing individually negociated involvement, Japan practising negociated involvement at the level of the (large) firm, Germany carrying it out at the industry level, and Sweden finding itself closest to the Kalmarian axis. What then is the attractive power of these axes? The experience of the United States shows that it is difficult to negociate involvement at the level of the firm in a flexible liberal context, however individually negociated involvement can be carried out there. Towards the other extreme West Germany appears to have a less socially advanced form of the Kalmarian paradigm. Japan appears to occupy an intermediate position which could be called "Toyotism", with a strong duality (rigid/flexible) in its external labour market.

II -THE NEWLY INDUSTRIALIZING COUNTRIES: WHERE ARE THEY GOING?

In parallele with Fordism, some late capitalisms of South America experienced a vague imitation of this model : "Cepalism" [6]. And young nations who became independant after World War II imitated that model or the Soviet model (India, Algeria) : in any case an "import substitution" strategy. Import-substitution was financed by experting raw-materials. After some real successes in the forties, fifties and early sixties, that model experienced difficulties that led to the Korean and Brazilian coups d’Etat (in 1962 and 1964), and then to its general abandonment in the eighties. In fact, new models of industrialization had developed, which were going to booster globalization again.

The 1970s witnessed the development of the Newly Industrializing Countries (NICs). Brazil and South Korea are the most important examples. Certain aspects of their development models have been examined elsewhere under the rubric of "primitive Taylorization" and "peripheral Fordism" (LIPIETZ [1987]).

× Primitive (or bloodthirsty) Taylorization. This concept is concerned with the relocation of limited sections of industries to the social formations with very high rates of exploitation (as concerns both wages and the length and intensity of work etc), the output being in general exported to the more advanced countries. In the 1960s the free zones and the workshopstates of Asia were the best illustrations of this strategy, which is expanding today. Two characteristics of this regime should be noted. First the work in general follows Taylorist principles, but there is relatively little mechanisation. The technical composition of capital in these firms is particularly low. This strategy thus avoids having to import investment goods, which is one of the inconveniences of the import substitution strategy. Another aspect is that since it mobilises a largely female workforce, it incorporates all the knowledge gained from domestic patriarchal exploitation. Secondly this strategy is "bloodthirsty" in the sense that Marx talked of the "bloodthirsty legislation" on the eve of English capitalism. To the ancestral oppression of women, it adds all the modem arms of anti worker repression (official unions, a lack of social rights, imprisonment and torture of opponents).

× Peripheral Fordism. Like Fordism it is based on the combination of intensive accumulation and the growth of final markets. But it remains peripheral in the sense that in the world wide circuit of the industries, skilled labour (especially in engineering) remains to a large extent external to these countries. Further, the outlets follow a particular combination of local consumption by the middle classes, a growing consumption of durable goods by the workers and low priced exports to the core capitalisms.

Take the two examples of Brasil and South Korea. Brazil started its industrialization earlier and with greater success than India, or Algeria. Agricultural reform was just as limited as it was in India, the supply of the reserve army of labour was Lewisian [7] and, since the Vargas period (during the Second World War), a Cepalist policy of import substitution led by the state has been put in place in the urban sector by the national capital. This was combined with corporatist social legislation (not that different from Fordist rules of the game). However there were two major developments which made a difference. First the developmentist state, while protecting its internal market from imports, did not hesitate, under Jocelino Kubitschek, to open the doors to capital and to technology from the "North West of the World". Next, the 1964 military take over suppressed the social advantages of the Vargas legislation. As a result the "scientific organization of work" developed without any limit other than technological dependance, and the bloody repression of the unions offered capital a "flexible" labour force. At the end of the 1960s and the beginning of the 1970s Brazil developed a very competitive industry, completed its import substitution and developed its industrial exports.

This led to primitive Taylorization. However Brazil did not clearly follow a simple strategy of export substitution. The investment goods were mainly paid for by the export of primary products and by borrowing. The benefits of primitive Taylorization were reinvested in the development of a dualist peripheral Fordism. A fraction of the population - the new middle class - set themselves up with a quasi fordist life style. The workers benefited in the second half of the 1970s from the productivity growth resulting from the mechanisation and rationalisation. This fraction comprised the major part of the "formal sector" (AMADEO and CAMARGO [1995]), which at the end of the 1970s had regained some of the advantages guaranteed by the Vargas legislation. But on the other hand there was a large section of workers who remained excluded from the benefits of the Brazilian miracle - the "Lewisian" ex peasants, the informal workers and the badly paid formal workers in small firms.

In the 1980s the debt crisis blew up, followed by a movement towards democracy (1985). The resulting evolution is fairly complex. On one side the democratisation increased the negotiating power of the workers and their legal guaranties, but on the other side high inflation reduced their ability to control the evolution of their real wages. Distributional conflicts were at the forefront of industrial conflicts. Labour relations could not stabilize in this permanent storm involving the marginalised Lewisian reserve army, the informal sector and the different levels of the formal sector. In this chaotic situation, the general evolution was a return to primitive Taylorization rather than a consolidation of peripheral Fordism. The worker’s aristocraty was "flexibilized", investment in health and education were abandoned.

In comparison, the 1985-87 revolution in South Korea inherited a much better situation. At the base of everything is the agrarian reform of the 1950s followed by income support for peasants. Primitive Taylorization in Korea was not under the pressure of a Lewisian reserve army. All the labour force was hired with a flexible work contract, but was formally hired. Moreover the State was careful to painstakingly plan export capacity to ensure that debt could be repaid. Women were terribly over exploited, especially in the export sector, but workers family incomes grew throughout the 1970s and accelerated in the 1980s. With the result that Korea saw a transition from primitive Taylorization to peripheral Fordism. Moreover among the male working class entreprise consciousness developed in such a way that it could lead to the copying of certain aspects of the Japanese form of negociated involvement at the enterprise level (YOU [1995]). The democratisation process will probably encourage these tendencies, since there is no longer any debt constraint, though there is still a competivity constraint. Korea could evolve towards a form less and less peripheral of Toyotism.

Thus, in the South too, globalization allows for at least two very different ways to compete.

III - THE COEXISTENCE OF POST-FORDISMS AND THE THIRD INTER-NATIONAL DIVISION OF LABOUR.

When at the beginning of the 1980s the Fordist compromise was openly criticised and judged obsolete, the spontaneous tendency was, once again and following the lessons of history, to look for "the" new form of hegemony in the capital-labour relations. The first part of the decade, marked by the success of Reaganism, saw the triumph of the idea that "the" way out of the crisis of Fordism would be the (external) flexibilization of the wage contract. "Euro-sclerosis " was criticised and blamed on the rigidity of the wage relationships. Then, after the crash of 1987, the decline of the United States and the impasse it had been led into by Reagan’s "deregulation" became obvious, and the technological and financial superiority of Japan and Germany became clear. It was recognised that models based on the "mobilisation of human resources" out-performed those based on flexibility. Today (in 1996), the difficulties faced by Germany and Japan show that things are not so obvious, and competition from the NICs of Asia and even Latin America seem capable of imposing on the whole world a single standard of ever lower wages and ever more flexible wage contracts.

In any case, is it reasonable to think that one of the two paradigms distinguished in the first two sections of this chapter will have an absolute advantage over the other and will end up by eliminating it ? The fact that it is not yet possible to say which one must however give us pause. First it is clear that the two paradigms are not sufficient to define a coherent model of development for the whole world. There is a lack, at the very least, of a mode of regulation of international effective demand. Competition in the world market has become global and the world market behave as a single competitive, hence cyclical, market, as it was before 1950. There is no reason why the cycles should spare the dominant model (be it the USA, Germany or Japan). Next, exceptional events such as the dissolution of the "socialist" bloc and its conversion into market capitalism, for the moment successfully in China and unsuccessfully in Europe, cannot but influence the economic situation and even the structure of neighbouring countries (especially the unification of the two Germanies).

But even taking into account these conjunctural considerations, we are prepared to risk the following structural hypothesis. The world will organize itself into three continental blocs, and within each there will be a division of labour between a centre and a periphery, based on different combinations of the two basic paradigms of post-Fordism.

The first point - the tendency for the world economy to break up into continents (Asia and the Pacific around Japan, the Americas around the United States, and Europe around Germany)—is not essential to the argument. This integration within continents results in the first place from a "revenge of geography" - with the "just in time" method of organization, distance and transaction times take on greater significance. It is also the result of the attempts to control the international economy, which on a world scale is to difficult to achieve, but which has got some chance of success between neighbours [8].

Within each of these blocks there are clearly countries at quite different levels of development with core-periphery type relations between them. These hierarchies are changing, there is progress in the peripheral countries, the dominant countries get out of the crisis with varying degrees of success, and above all they use different ways to do so, emphasising one or the other of the paradigms shown on the axes defined earlier.

The second hypothesis put forward here is thus the possibility of the coexistence of the two paradigms within the same area of continental integration, with an international division of labour of the third type between countries where one or the other of the two paradigms dominates [9]. Note that itis not a question ofproducingindifferent ways quite different products as in the first international division of labour, nor to specialise, as in the second international division of labour, in different kinds of task within the same paradigm and within the same industry, but rather to produce similar products in a different way.

This is only possible if neither of the two paradigms completely outperforms the other, which one dominates depends on the industry or sub-industry. At this point the Ricardian formalism finds its heuristic value if the notion of "initial endowment of factors" is replaced by that of "social construction of the adoption of a paradigm". This social construction is a complex fact about society that is not elaborated here. Here it is simply noted that the adoption of the "flexible" and "negociated involvement" paradigms correspond, respectively, to "defensive" and "offensive" strategies, on the part of the elites of the nation or region considered, for getting out of the crisis (LEBORGNE and LIPIETZ [1991]).

This can be put as follows (adapting Ricardo’s theorem) : the industries most sensitive to skill will tend to look for the relatively more skilled (and less flexible) segments of the world labour market, the industries most sensitive to the low cost of labour will tend to look for the more flexible segments of the world labour market.

This helps to understand the success of the "Toyotist" model, because if within a given society the two types of labour market can be found, then the ability to negociate wages at the level of the firm would enable there to an optimal adaptation for all industries. The more "Kalmarist" national models are handicapped by the rigidity and excessive cost of labour in the most standard industries. The most flexible national models (neo-Taylorist) are handicapped in industries requiring a high level of skill. On the other hand countries where there is a classical Fordist relation (rigidity plus Taylorism) will be gradually out performed "from above and from below".

Industries with the most skilled labour will tend to be found at the top and the right of figure 2, where there will be high salaries, high skill levels, the highest internal flexibility and hence the greatest ability to introduce new processes and to invent and test new products. In a word it is in "core" countries. As industries become more standard, they are found in countries more and more to the bottom and left of the figure, who can remain competitive only by a more and more savage flexibility and with ever lower wages, and with the risk of being accused of "social dumping". Figure 2 shows how you move down the steps towards the periphery : first you find the old fordist countries becoming and more neo-Taylorist, then the peripheral fordist countries, then primitive Taylorization countries...

IV - SOCIAL CONSEQUENCES OF GLOBALIZATION : UNCREASING UNEQUALITIES

As we have seen, two strategies of economic development are now competing all around the world. The "wining one" (negotiated involvement of the workers) is wining only in some priviledged sectors or sub-sectors. On the other hand, the out-performed strategy (flexibilization) can compete at a sufficiently low wage and sufficiently high degree of precarity of labour contracts. As a general result, all the unskilled or semi-skilled labour of the world is now actualy in competition. For these workers, it seams than neither the social-democratic nor the corporativist-populist (cepalist) compromises of the 1940’s could hold anymore. The result is a global downsizing of the share of labour in the global value-added. This general law is well known through the UNEP studies on "World human development", its national translation is well known in the Brazil of the eighties-nineties. But let us have a glance to Advanced Capitalist Countries.

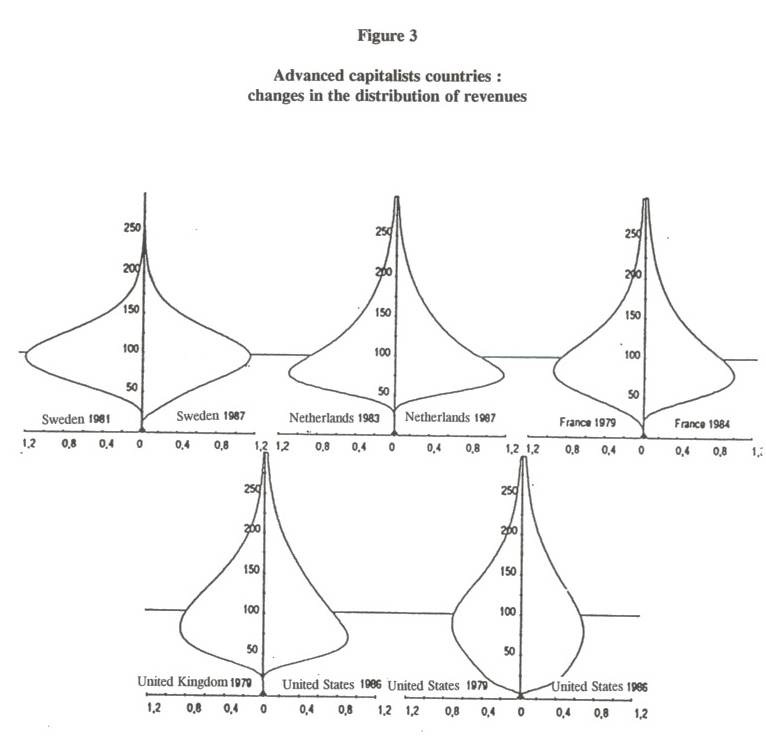

On figure 3, the distribution of revenues is represented as strobiloids ( from the greek strobilos, spinning top). On the vertical axis is represented the level of (after-tax and welfare) revenue per household, compared to the national median (index 100). On the horizontal axis is represented the share of population, the surface being normalized as constant (the same for any year and any country). The figure shows the strobiloids for some ACC, the left part at the end of fordism (end of the 70’s), the right part some years later.

In the left parts of figures (around 1979), Sweden, Netherland, France and UK appears as degrees of social-democracy : no real poors, few riches, a huge concentration of revenues around the median. USA (the official homeland of middle-class and Fordism) are already a little more "brazilian". Five years later, the picture has already changed (right part).

A major difference is obvious. Some strabiloïds are more or less the same, like Sweden, while Netherlands and France have even increased the relative revenue of the poors. France is experiencing in 1984 the first phasis of its "socialist" experiment (more on France later). On the contrary, UK has initiated a downsizing of the revenue of its poorer half. In USA, the "brazilianization"1 [10] of society is already more advanced : there are many people with a revenue between "nothing" and "very few".

This divergence between two typical situations is the social translation of the divergence between national post-fordisms shown on figure 1. Unfortunately, we have no such strobiloïds for the post-fordist area. Yet a more qualitative study by K. Gardiner [1993], on national quantitative data, confirms the tendency all along the eighties :

– There are countries where unequalities in revenues, which had decreased in the seventies, are now stable (Italy) or mildly increasing (Germany, Japan, Sweden). They are the homeland of "negotiated involvement".

– There are countries where unequalities increase strongly in the eighties : UK and the USA (where actualy they have been increasing as soon as the seventies). In these homelands of "flexibilization", that is the result of three tendancies :

– Increase of property-revenues by comparison to labour-revenues.

– Decrease of (per household) welfare revenues.

– Increase of unequalities within wage-earners, between highly skilled workers and executives on the one hand, unskilled and precarious workers on the other hand.

In fact, unskilled or semi-skilled workers are more and more in competition with third world workers. A typical metal-worker of the U.S. Midwest would earn 24 dollars per hour in the early eighties, his/her substitute would earn half this price in Ohio at the end of the eighties, and is still in competition with a 4 dollars worker in Brazil1 [11]. In the case of British (welsh or scotish) workers, they are now less expensive than Korean ones : Korea appears to be more to the right-top end of the curve than UK in figure 2.

According to Laura d’Andrea Tyson (1994), the distribution of revenues per household, represented by slices of 20% of the population (a logics in representation different from strobiloids), has moved the following way in the post 1973 United States :

| Slices of 20% | Growth of annual revenue of the slice (cumulated 1973-1992) |

| First (lowest) | - 12 % |

| Second | - 3,5 % |

| Third | + 3,7 % |

| Fourth | + 9,9 % |

| Fifth (highest) | +19,2 % |

Let us turn now to the french case. Contrary to USA, France experienced a social-democratic management of its turn towards neo-liberal flexibility after 1983. Thus, while its pre-tax, pre-welfare distribution of revenues presents the anglo-saxon evolution to brazilianization, the after-tax, after-welfare distribution remains basicaly the same in 1990 as in 1982 or even 1975. This is due to the full-effect of an extensive retirement system created in 1945 (and thus producing complete retirement pensions forty years after), and to the creation in 1988 of a waranted minimum revenue, around 500 US dollars a month per adult (LIPIETZ [1996b]). But the classical "hour-glass" distribution of revenues is obvious, precisely when considering the pre-tax, pre-welfare distribution : riches becoming richer and richer, shrinking middle-classes, increasing proportion of very poor households.

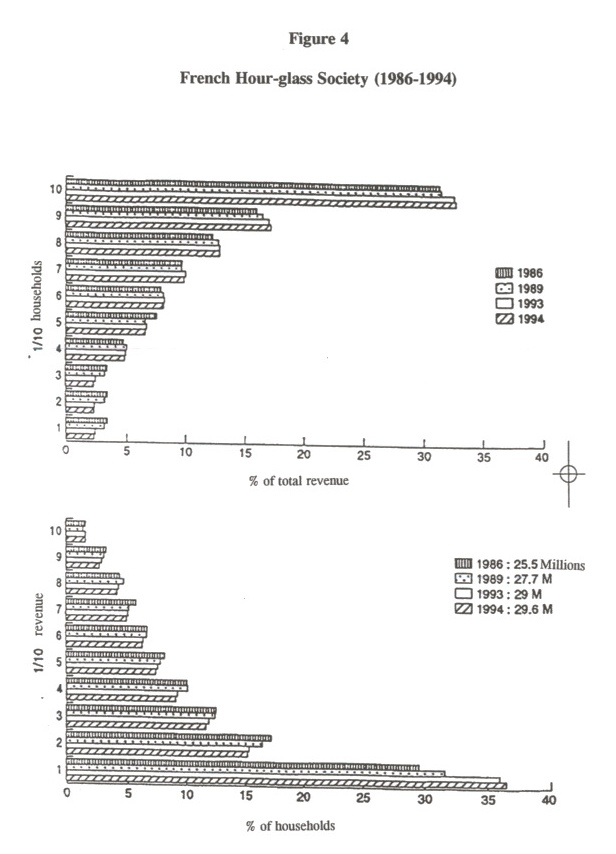

The Figure 4 expresses these tendencies.The statistical basis is taken from the taxable revenue-declarations, which are aproximatively declared by household1 [12]. The top part of the figure is ordered by slices of 10% of the declarations of growing revenues, and the length of horizontal bars represent the share of total revenue accruing to households of the slices. Years after years the upper part grows, while the share of 30% of lower revenue households shrinks from 10% in 1986 to 7.05% in 19941 [13].

The bottom of the figure is ordered by slices of 10% of the total revenue of households, and the length of the bars represent the share of the total number of households corresponding to each slice. While the number of households sharing the 10% highest revenues does not change significantly around 1.56%, the huge "middle" shrinks clearly, and the lower part of french population of households sharing 10% of total revenues increases rapidly : from 29.7% in 1986 to 31.6% in 1989 and 36.5% in 1994.

The superposition of the two figures makes clear why that kind of social evolution is compared to an "hour-glass", where grains of sand represent households, desperately falling to the bottom.

V - THE GLOBAL ECOLOGICAL CRISES1 [14]

A "global ecological crisis" is a crisis the causes of which are diffuse and the effects of which are universal. From the economic point of view, a global crisis is much different from local crises. In local crises, such as river-pollution, trafic jams, or soil erosion, local agents are usually directly accountable for damages to local victims (frequently the same individuals). By contrast, in the ecological global crisis, the "culprit" may be nothing less than a model of development encompassing whole continents, and "victims" may be in other continents with other styles of living. Clearly, globalization and its "brazilianizing" social effects have undirect local ecological effects, since poverty is in se a cause of worsening of environment, be it in a favela or in the sertao, in shanty-towns or in semi-arid over-worked countrysides. But we are here going to considere the way differenciated industrial strategies within globalization foster different attitudes towards global ecological crises. Let us take the case of greenhouse effect.

There was a quasi consensus in the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC Report 1991) that, for a doubling of CO2 concentration in the atmosphere (or equivalent quantities of other Green House Gases - GHG), the rise in average temperature would be : 3°C ± 1.5°C. This large uncertainty for a physicist is not so relevant for international relations : a rise of + 1.5° C would already be a major problem (and + 4.5° C an inconceivable crisis)! Uncertainty also exists on when such a concentration would be reached, but, at the present rate of emissions, it is agreed that it is a question of more or less half a century.

What would be the effects of a + 3°C increase ? Still more imprecisions here, but the fact that we don’t know exactly the physical effects does not entail that we do not know who would be economicaly the relatively "worse loosers". In fact :

* First, weather will be globally wetter, but water will be less useful on the ground, for it will evaporate faster, or will erode the soil more violently. This "tropicalization" of the world is likely to be detrimental to countries of the geographical South relying heavily on agriculture and with a large peasant population.

* The sea level will increase (through dilatation) by some 30 to 50 cm. A disaster for countries with large sea-shore populations : deltas, islands, etc.

Clearly, most victims are de facto in the "social South" : India, China, Bangladesh, because of the sea-level rise ; Southern America and Africa would join the list because of changes in conditions for agriculture.

By contrast, a country of the North like USA, though being a powerful agricultural country, but with only one semi-desert delta, has a weak "interest" in fighting green-house effect. That was perfectly illustrated in a quite standard economic demonstration by Nordhaus [1990]. Admitting a doubling of CO2 in 40 years with a Green House Effect of + 3°C, Nordhaus first identifies its cost (for USA) with the fall in production in various sectors, principally agriculture. The later being of less and less importance in US economy, the cost will be very low (-0,25% in expected GDP). Then, he discounts this cost at a rate of 4%. Not surprisingly, such a low cost will justify few anti-GHG immediate actions. In his words, it would be "unwise" to seek for more than a marginal reduction (-13%). An ecotax of $ 5 US per ton of carbon, that is 58 cents per barrel of oil, would be "cost-effective".

Anyway, Nordhaus illustrates quite well one possible theorization for a possible attitude of Northern countries : "Do Nothing". It could seem that the normal attitude of Southern countries should be "Do Something". The conflict should present itself as the South trying to protect its climate against the Northern pollution by GHG. But the reality of negotiation on climate was and is still quite different. In order to understand this paradox, we have to introduce a more realistic representation of North and South.

The first elaboration we may propose is a closer scrutiny to the costs of "Doing Something", and not only to its advantages (that is : to the damages of "Doing nothing"). To my knowledge the most impressive systematic attempt is the study by Benhaim, Caron & Levarlet [1991] (later : BCL). They chart 50 countries (including most of OECD and Eastern Europe, the main Third World countries) by automatic taxonomic methods according to 20 criteria. The result is quite interesting, both when it confirms actual similarities of attitudes in the Climate negotiation and when it contrasts with reality.

The first group of indicators includes GDP per capita and the Index of Human Development (PNUD 1988). They are static indicators (by contrast to rates of growth), neutral with respect to population. All other indicators are linked to the energy system : type of energy used, indices of consumption of primary energy, of energy efficiency, of energy reserves, of CO2 emissions, per Capita, per unit of GDP, per country. Note that the last one is not neutral with respect to the size of population, just as energy reserves is not neutral with respect to the surface of the country. Also note that there is no index of "advantages in doing something" (such as : share of peasantry, share of population living at sea level).

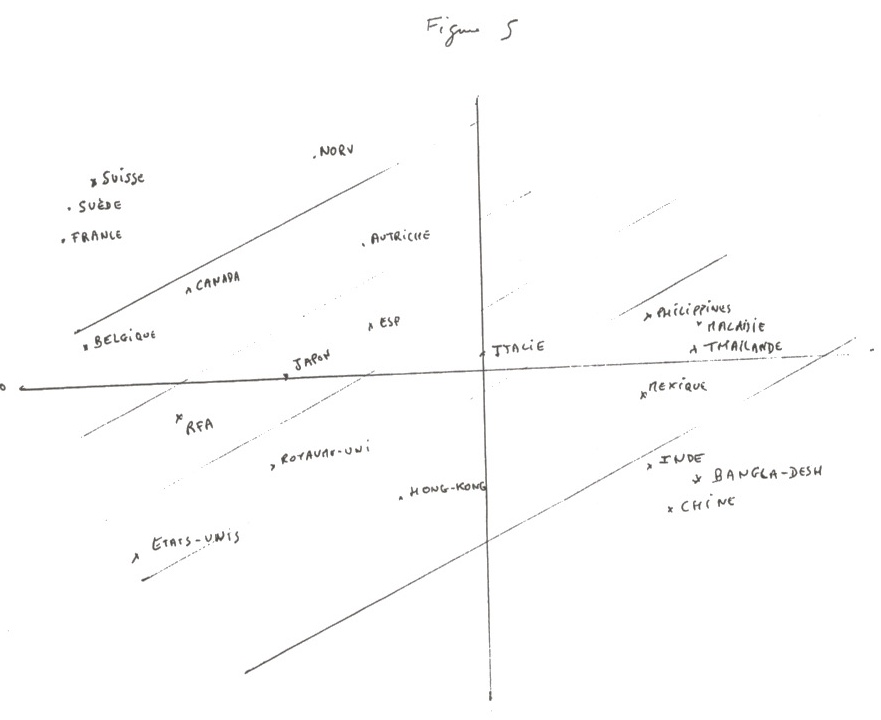

BCL proceed a classification of countries via principal components analysis (Figure 5). The first axis in the analysis presents an opposition between "development" (on the left) and "underdevelopment". Development is positively correlated to :

– energy-consumption per capita

– CO2 per capita

– share of nuclear in energy

and negatively to :

– coefficient of CO2 per unit of GDP

– share of hydrocarbons

– reserves of hydrocarbons.

In other words, the more a country is developed, the more it consumes energy per capita and thus the more it emits CO2 though the more GHG-efficiently it produces its energy.

On the second axis, the criterion of "cleanness" (relative to GHG) of production is illustrated, opposing GHG-efficient use of electricity, at the top, to GHG-polluting use of carbon, at the bottom.

Combining these two axes, a "virtuous" hierarchy, from the top-left to the bottom-right appears. The "GHG virtuous" are, on the first line, Swiss, Sweden, even France (because of nuclear power !) then other Scandinavian countries, Canada, Belgium, then RFA and Japan, then USA and UK, Spain...

In a very expressive way, this chart isolates, in the top-right of the chart, countries which are both rich and GHG-efficient in the production of their energy : the "super-virtuous" of Scandinavia, the "virtuous" Japan and EEC (less so in the cases of UK and Spain). These countries are ready to implement the precaution principle : they have or can get the technologies, they are already at a relatively low (yet unsustainable) level of emissions.

By contrast, USA appears in the bottom of the chart, along with fossil energy wasters : ex-Socialists countries, South-Africa and China. In these countries, along with Petromonarchies, welfare is correlated to GHG-wasting. They are in favour of what BCL label : the blockage strategy. Georges Bush, with his Rio statement "Our way of life is not subject to negotiation", illustrates this position.

Very different in appearance are the countries in the midde or bottom-right of the "GHG-virtuous" diagonal : India, Brazil, Mexico, China, Malaysia. These countries are too poor to be already GHG-dangerous and to be GHG-efficient. But clearly they dream to be as "developed" as Western Countries, and consider that up to now these precursors never implemented any precaution principle. These countries are pushed into an accusation strategy : denouncing the responsibility of the North-West of the World in the past for the concentration of GHG in the atmosphere, such a strategy contends that it is not yet time to implement a precaution principle in Developing Countries.

The amazing fact is that Figure 4 broadly appears as a 90° counter-clockwise rotation of figure 2. Within the globalization process, the ranking of national trajectories vis-à-vis capital-labour relations (more or less crude or negotiated) appears to be in correspondance with the ranking of their attitudes vis-à-vis global ecological problems (more or less blockage or precaution). A similarity about which one can rely only upon broad intuitions : effects of culture, history, politics...

If we now cross the two criteria (advantages of "Doing something", and costs of "Doing something" analysed in figure 4), the North-South conflict appears now much more complex.

Along the two criteria, the position of USA is clearly in favour of "doing nothing" : the dangers from greenhouse effects are weak, the cost of fighting it may be very high, even if the low GHG-efficiency of their energy-production makes the marginal improvements quite inexpensive. The problem is that, from a global sustainability point of view, the improvements required from USA are far from marginal. A "sustainable" GHG production is thought to be 500kg per capita and per year. USA produce 5 000kg.

The radical accusation strategy seems to be the opposite, and indeed its glamour in a North-South conflict is very attractive : "You are the culprits, you have to do everything". The problem is that this position is a blockage position just as well, since it is subordinated to the implementation of a precaution strategy by foreign countries which are in favour of blockage. It is quite appealing for elites who dream to imitate the US model of development (a savage capitalism in an open frontier land) and which are not too much worried by the consequences of green-house effect on their own population. Here, it is important to notice that an international negotiation involves governments, that is elites, and not peoples. The position of a government may be quite different from it’s people interests if the political regime is rather independent from civil society.

Malaysia is a good example satisfying these criteria. The Prime minister Mohamad Mohaytir did not hesitate to put it in the Asian Society Forum 1991 : "Democracy, human rights, ecology, unions right, are but obstacles that advanced countries try to put on the road of their future competitors".

So we have in fact two types of "Do-nothing positions" : the one of the North (fighting greenhouse effect is too expensive and useless for us) and the one of the South (fighting greenhouse effect would unfairly hinder our development, and the results of global warming are irrelevant to us).

But our discussion indicates two classes of potential followers of a precaution strategy. The first one includes the nations which have serious reasons to believe that they would be the first victims of global warming : Bangladesh, Maldives, India, Africa, South America. When, moreover, they are countries wich are both low producers of GHG (much less than the "sustainable" 500 kg/capita) and quite GHG-inefficient, they may assume that their contribution to world production may increase for a while without being a real problem.

Symetrically, we noticed that Japan and E.U. are Northern countries which may think of decreasing their GHG-production. Producing less than 2 tons per capita, and evolving towards a "service society" with a steady population, they may think that the 500 kg target is within their scope. When, moreover, they are countries particularly sensitive the dangers stemming from demographic and ecological turmoil at their southern borders, they may assume that a precaution strategy is relatively inexpensive and really useful. Moreover, inner ecological militancy begins to frame their politics.

CONCLUSION

Within globalization of economies and capital-labour relations, several territorial strategies have developped. Some rely on flexibilization and polarization of skills and revenues. Some rely on negotiated involvement of labour, skilling and social solidarity. The relative competitiveness (in the longt-term) of the two tendancies is still an open discussion. Yet Japanese, North italian, German and Korean experiences prove (at least into the nineties) that the second strategy may combine social progress and competitivity.

More mysterious is the connexion between social successes and ecological responsability. Of course, one may suspect that a society which cares for the health, education, skilling and revenues of its poorest would be more inclined to care for sustainability and future generations than a society who resists to invest in human capital at the present generation. But more investigations are required to strengthen that intuition.

BIBLIOGRAPHIE

AGARWL A., NERAIN S. [1991]

Global Warming in an Unequal World : a Case of Environmental Colonialism, Center for Science and Environment, New Delhi.

AMADEO E., CAMARGO J.M. [1995]

«New Unionism and the Relations between Capital, Labour and the State in Brazil» in Shor & You (eds).

AOKI M. [1990]

« A New Paradigm of Work Organization and Coordination: Lessons from Japanese Experience » in Marglin & Schor (eds).

BENHAIM J., CARON A., LEVARLET F. [1991]

"Analyse économique des propositions des acteurs face au problème du CO2", Cahiers du C3E, Univ. Paris I, Mimeo.

BOWLES S. [1985]

« The Production Process in a Competitive Economy: Walrasian, Marxian and Neohobbesian Models », American Economic Review, 75.1 (Mars), p.16-36.

D’ANDREA TYSON [1994]

Economic Report to the President, Washington DC.

DOERINGER P.B., PIORE M.J. [1971]

International Labor Markets and Manpower Analysis, Sharpe, New-York (revised 1985).

GARDINER K. [1993]

«A survey of Income Inequality Over the Last Twenty Years. How Does the UK compare ?», STICERD Discussion Paper, WSP/100, London.

GLYN A., HUGUES A., LIPIETZ A., SINGH A. [1990]

« The Rise and Fall of the Golden Age », in Marglin & Schor (eds) [1990].

LEBORGNE D., LIPIETZ A. [1988]

« New Technologies, New Modes of Regulation: Some Spatial Implications », Space and Society, vol.6, n°3, 1988.

LEBORGNE D., LIPIETZ A. [1991]

« Two Social Strategies in the Production of New Industrial Spaces», in Benko & Dunford (eds), Industrial Change and Regional Development, Pinter Publ. Belhaven Press, London, 1991.

LEBORGNE D., LIPIETZ A. [1990]

« Avoiding Two-Tiers Europe », Labour & Society, Vol 15 n°2.

LIPIETZ A. [1985]

The Enchanted World, Verso, London 1985.

LIPIETZ A. [1987]

Mirages & Miracles - Crises in Global Fordism, Verso, London.

LIPIETZ A. [1992]

Towards a New Economic Order, Posffordism, Ecology, Democracy, Polity Press - Oxford U.P., Oxford - New York.

LIPIETZ A. [1994]

« States and Regions in the Face of the Global Capitalist Crisis», in Palan & Gills (eds), Transcending the State Global Divide, Lynne Rienner, Boulder (COL).

LIPIETZ A. [1995]

«Enclosing the global commons : global environmental negotiations in a north-south conflictual approach» in Bhaskar & Glyn, The North, the South and the Environment, Earthscan, London.

LIPIETZ A. [1996a]

«The New Core-Periphery Relations : The Contrasting examples of Europe and Americas », in Naastepad & Storm (eds) The State and the Economic Process, Edward Elgar, Cheltenham (UK).

LIPIETZ A. [1997]

«The Planet after Fordism », Review of International Political Economy, Forth coming.

LIPIETZ A. [1996b]

La Société en sablier, La Découverte, Paris.

MAHON R. [1987]

« From Fordism to ? New Technologies, Labor Market and Unions », Economic and Industrial Democracy vol.8 pS-60.

MARGLIN S. & SCHOR J. (eds) [1990]

The Golden Age of Capitalism: Reinterpreting the Postwar Experience, Clarendon Press, Oxford.

NORDHAUS W.D. [1990]

"Economic Approach to Greenhouse Warming", présentation to the Conférence Economic Policy Response to Global Warming, Rome, 4-6 Octobre.

PIORE M.J., SABEL C.F. [1984]

The Second Industrial Divide: Possibilities for Prosperity, Basic Books, New York.

SCHOR J. & YOU J.I. (eds) [1995]

Capital, the State and Labour A Global Perspective, Edward Elgar, cheltenham (UK).

WORLD RESOURCES INSTITUTE [1990]

World Resources 1990-1991 : a Guide to the Global Environment, Oxford U.P., Oxford.

YOU J.I. [1995]

« Changing Capital-Labour relations in OECD », in Shor & You (eds) Projet WIDER.

NOTES

[1] The sub-section which follows is a synthesis of Glyn et al [1990], Lipietz [1987, 1992].

[2] See Aoki [1990]. A long time ago Andrew Friedman [1977] had already opposed "responsible autonomy" and "direct control" as being two tendencies which were in permanent conflict within capitalist organization of work.

[3] The final part of this section and the following one is the result of a collective work organised at an international level by the World Institute for Development Economics Research, now published as SCHOR & YOU (eds) [1995], and of previous works by LEBORGNE & LIPIETZ [1988, 1991, 1992]. See also MAHON [1987].

[4] Or even at the international level! The problem of which geograpic field is suitable to the social paradigms is one of the most difficult and least explored (see however Lipietz [1994]).

[5] This combination is still however possible if it concerns different segments of the labour market within the same society (for example : men/women). What is in general not possible is the negociated involvement of a group of flexible workers. That is to say the Piore and Sabel model.

[6] "Cepalism" : from the spanish acronyme (CEPAL) of the Economic Commission for Latin America of U.N., where economists such as Raoul Prebish inspired this policy.

[7] Lewisian : from the name of Arthur Lewis, who identified in the Third World situations were, at any price, labour supply is infinite in relation to labour demand.

[8] On the contrasting macroeconomies of the three blocks, see Leborgne & Lipietz [1990], Lipietz [1996a, 1997].

[9] The first I.D.T. opposed countries (of the North) exporting manufactured goods and countries (of the South) exporting raw materials. The secondI.D.T.opposed, within Fordism, countries specialized in engineering and design and countries specialized in low-skill productions. See Lipietz [1987].

[10] On "brazilianization" of USA, see Lipietz [1987].

[11] Data from Bendix, a multinational company based in South Bend, Indiana, USA.

[12] Some non-maried spouses, some adult children, declare separately. The "taxable revenue" is already reduced by social security contributions, and increased by retirement pensions. But all that is proportionnel to wage and thus does not change distribution.

[13] It was impossible to separate the three lowest tenth of the households.

[14] This section is a synthesis of LIPIETZ [1995f].

-

[18 juillet 2014]

Gaza, synagogues, etc

Feu d’artifice du 14 juillet, à Villejuif. Hassane, vieux militant de la gauche marocaine qui nous a donné un coup de main lors de la campagne (…)

-

[3 juin 2014]

FN, Europe, Villejuif : politique dans la tempête

La victoire du FN en France aux européennes est une nouvelle page de la chronique d’un désastre annoncé. Bien sûr, la vieille gauche dira : « (…)

-

[24 avril 2014]

Villejuif : Un mois de tempêtes

Ouf ! c’est fait, et on a gagné. Si vous n’avez pas suivi nos aventures sur les sites de L’Avenir à Villejuif et de EELV à Villejuif, il faut que (…)

-

[22 mars 2014]

Municipales Villejuif : les dilemmes d'une campagne

Deux mois sans blog. Et presque pas d’activité sur mon site (voyez en « Une »)... Vous l’avez deviné : je suis en pleine campagne municipale. À la (…)

-

[15 janvier 2014]

Hollande et sa « politique de l’offre ».

La conférence de presse de Hollande marque plutôt une confirmation qu’un tournant. On savait depuis plus d’un an que le gouvernement avait dans (…)

-

[11 May 2016]

Dans l’état où nous sommes...

Allergique à Fesse-bouc je me permets de commenter ici votre article "Dans (…) -

[17 December 2015]

Cliquez sur le smiley choisi

May I just say what a comfort to discover an individual who genuinely knows (…) -

[18 July 2015]

Démocratie grecque

Cher Joke, dernier dialoguiste de ce site (qui reste très lu) Je ne dis pas (…) -

[9 July 2015]

Démocratie grecque

Puisque je suis sur votre blog, pour les félicitations, je vais en profiter (…) -

[9 July 2015]

Gaza, synagogues, etc

Félicitations aux mariés ! Et longue vie (militante) ensemble. (Je renonce à (…)

- 1995 à 1999

-

[2012年9月5日]

Regulationist political ecology or economics of environment ? -

[Julho de 2003]

A ecologia politíca e o futuro do marxismo -

[1 March 2000]

Political Ecology and the Future of Marxism -

[16 décembre 1999]

Epargne salariale et retraites.Une solution mutualiste -

[septembre 1999]

La valeur travail en débat - Écologie politique

-

[24 novembre 2024]

L'autonomie au coeur de la revendication écologiste -

[24 septembre 2024]

Après le désastre des élections européennes, face au défi. -

[18 avril 2024]

Futur antérieur -

[18 avril 2024]

Interview d'Alain lipietz, tête de liste alternatif dans la Seine-Saint-Denis -

[21 mai 2022]

Penser l’écologie. Débat avec Bérénice Levet et Alain Finkielkraut - En anglais

-

[14 May 2022]

Lessons from the French Presidential Elections -

[12 October 2017]

FRANCE AND MACRON’S EUROPE -

[December 2015]

BENEATH THE SURFACE OF THE CRISIS: A CLOSER LOOK AT THE STATE OF FRENCH GREENS -

[February 2015]

POLICY IN A TIME OF MONSTERS: TEN THESES -

[31 January 2014]

The Anthropological Crisis and the Social and Solidarity Economy - Mondialisation

-

[23 June 2015]

Growth strategies, employment and job quality in a globalized world -

[15 avril 2015]

La trop évitable crise européenne -

[Mayıs 2012]

Korkular ve Umutlar: Liberal Üretkenlik Modelinin Krizi ve Yeşil Alternatif -

[1ro de diciembre de 2011]

Temores y esperanzas: la crisis del modelo Liberal-productivista y su alternativa verde. -

[26 septembre 2011]

Craintes et espérances : la crise du modèle libéral-productiviste et son alternative verte. - Social

-

[22 mars 2022]

Face à la toute-urgence écologique : la Révolution Verte -

[28 novembre 2020]

Comment ceux qui luttent pour la planète prennent-ils en compte les personnes qui attendent avec inquiétude la fin du mois ? -

[16 septembre 2019]

Ecologie politique des Gilets Jaunes -

[5 décembre 2018]

Écologie politique des Gilets Jaunes -

[5 de agosto de 2015]

Las políticas sociales en América latina : laboratorio mundial

-

[15 February 2013]

Fears and hopes: The crisis of the liberal-productivist model and its green alternative -

[5 febbraio 2013]

Un protezionismo universalista -

[21 de enero de 2013]

Transición energética: últimas posibilidades para Europa -

[13 décembre 2012]

Pour un protectionnisme universaliste -

[11 décembre 2012]

Transition énergétique : dernières chances pour l’Europe.